Lecture-performance by Gaston Meskens done in the abandoned salt mine in Hallstatt, Austria, at the Memory of Mankind site

The reflection “Fragments of Absence – the archive of our common future” was made there on invitation by Martin Kunze who initated and runs the ubercool ‘Memory of Mankind’ project. Wondering what would be the ultimate durable physical carrier to carry our knowledge and memories into the very far future, Martin developed a technique to print on ceramic tiles that can remain intact for the next million years (one small tile can contain the text of a whole book). The tiles are stored down in the salt mine in Hallstatt where they wait to be discovered somewhere in the far future.

The ‘Memory of Mankind’ project is purely democratic, which means anyone can contribute to deciding what knowledge should be archived, and if you want to support the project, you can order a tile containing your own works, thoughts and images to be preserved for eternity. Your tile will come in two copies: one for you and one that will be stored underground. Check it out: https://www.memory-of-mankind.com/

> – <

. Fragments of Absence .

(the archive of our common future)

Gaston Meskens

Hallstatt, 27 April 2022

> – <

[…]

What is the status of an artefact – a text, scheme, image, drawing or object – stored in an archive?

Is its meaning stored at the same place as the physical thing? Can it change meaning while left untouched in the dark for years? If the world moves on with time, can we say the artefact is ‘left behind’? Or is it ‘moving on’ too, taking context with it in its slipstream?

[…]

Today I invite you to reflect on the archive as a physical place that is still but not dead. While everything remains in place in the corridors, on the shelves or in the drawers and boxes, the meaning of what is stored, indexed and catalogued is continuously changing with time.

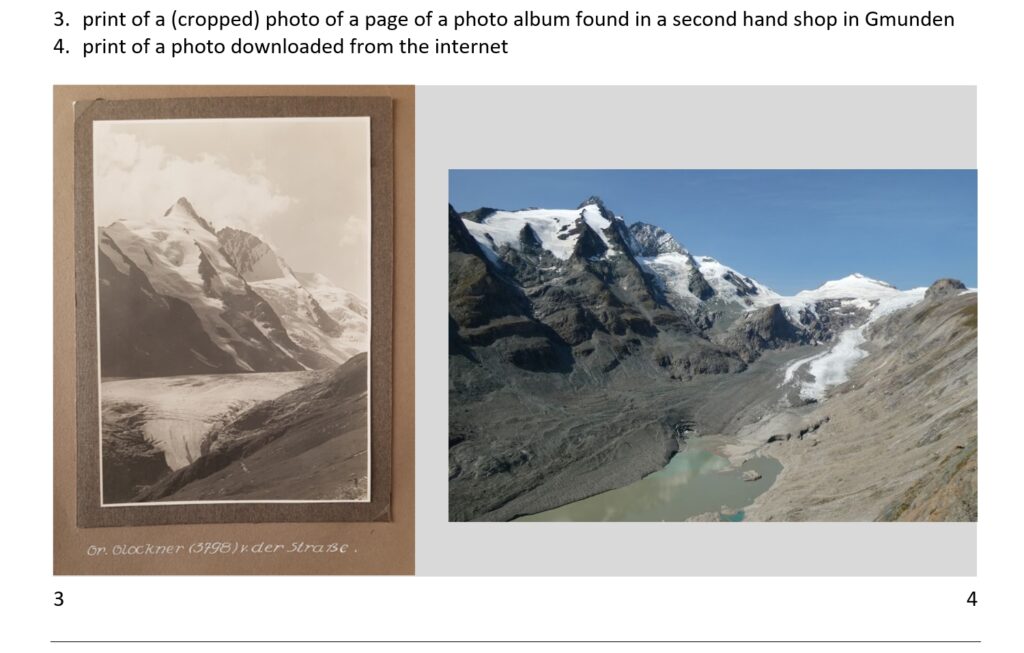

The question is whether we can possibly understand the past through the memories of it preserved. How can we look at historical artefacts today, knowing that we hold and observe them, naked, decontextualised from everything that surrounded them at their time of material realisation and through their years of use and later storage? Is contextual meaning lost or just absent? How could we reconstruct contextual meaning if it’s only present in its aura of absence? Where is the archive of absences needed to understand the past? And, last but not least, what if we think we do understand the past, and then we find an artefact – a text, scheme, image, drawing or object – that, without context, subverts or shakes up the whole picture of the world as we know it?

In trying to understand the past through the memories of it preserved, the questions raised above emerge from a position of ‘critical wonderment’. What is it that we see? Who has chosen to archive it, and why? The position can also be described as a reflexive awareness of the volatile character of contextual meaning of materialised ‘information’ of which the material ‘presence’ as such is elusive, even in a state of degradation.

The place where we are today reminds us that, while questions concerning the understanding of the past by way of physical artefacts require thorough reflection, the challenges coming with preserving memories from our present times for future understanding are even more difficult to tackle. Today we document our life with a constant stream of photos that go straight into the cloud. At the same time, zillions of chats and emails, whether trivial messages, functional communications, fictional stories or deeply emotional or spiritual thoughts, disappear in digital recycle bins or archive folders. In comparison with the era of the handwritten letter and the printed document and photo, we face today not only the challenge of distinguishing the essential from the overload, but also a paradox with regard to the possibility of human historical memory itself. On the one hand, storing images and text became easier than ever before. On the other hand, the possibility for the next generations to consult and study our records was never more uncertain. Already now, many of our records are lost, stored as they are on obsolete hard- and floppy disks and in no longer readable digital archive folders. Meanwhile, our document and image clouds and internet pages are in the hands of big private corporations who think profit and give no guarantee our memories will be preserved into the far future. As a consequence, in archiving our recent historical memory, we face not only the need to deal with the absence of contextual meaning but primarily with the absence – in the sense of the waning presence – of the artefacts themselves.

What can we learn from all this in the interest of dealing with our concern, namely to be understood by those from the future in dealing with our impacts on them? Martin’s Memory of Mankind project learns us that building the archive of our common future should be done through a continuous process of reflection and deliberation, always aware of two ultimate challenges

Firstly, it makes no sense to try to completely control the understanding of our messages in the far future. We can never provide ‘full context’, because our attempt to explain context is always done in its own context, and will anyway be open to interpretation from out of any possible context in the future. The first position of someone who would find our artefacts in the far future, whether it would be our objects or texts or the nuclear message, will always be wonderment; a priori wonderment before possible recognition and understanding.

The second challenge is very simple in principle: doing our best today in taking care of the long term effects of our actions that might negatively affect our fellow humans of the future. Only then, even facing this impossibility of providing full evidence and the guarantee of understanding of the traces we left, of what we did today, we can try to explain the far future that we tried to do our best, and why we thought this was the best we could do…

Gaston Meskens, Hallstatt, Memory of Mankind site, 27 April 2022